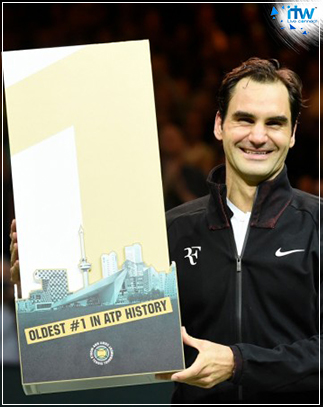

The oldest ever tennis player to hold the No. 1 ranking, Roger Federer’s longevity & sustained excellence are not only remarkable achievements but are a valuable lesson in strategy. Sustainable competitive advantage, every business’ holy grail, is hard to develop and harder to retain. Nothing from the world of sport illustrates it better than professional tennis, where individual players have to rack up consistent performances and be constantly better than their opponents to push themselves up the ranking ladder and succeed on court in the form of title wins which translates to earnings. They are, as tennis writer Carl Bialik described once, “individual contractors who have to cover their own transportation, equipment, coaching and — at some events — accommodation and food.” And they have to generate revenue through winning or through sponsorships to sustain themselves. Much like a business. Among those ‘businesses’, the current superstar is a certain Roger Federer who, at the age of 36, becomes the oldest player (male or female) to occupy the top spot in singles rankings. It’s a remarkable achievement because the last man who was the oldest – Andre Agassi at 33 – retired soon after. Federer still seems to have gas left in the tank. Even more remarkable is the fact that, Federer has been a professional for 20 years now, and first became No. 1 in 2004. But perhaps the most amazing stat of all is that he was last No. 1 almost five and a half years ago in 2012. His longevity is astonishing in a brutally competitive and unforgiving sport and tennis wise, there are many ingredients to the secret sauce of his sustained success. But even businesses could learn a thing or two. Especially if you are willing to use a lens called the RBV or the Resource Based View of the firm. First popularized in the 1980s by Birger Wernerfelt and becoming mainstream thanks to the concept of core competence introduced by CK Prahlad and Gary Hamel, RBV is a cornerstone of strategic management analysis looking at a firm as not the aggregate of the product or services it sells but as a combination of resources and capabilities. The theory posits that companies that build sustainable competitive advantage do do not by just selling better products or services but by putting themselves in a position where they can best exploit their internal resources and capabilities to take advantage of external opportunities and deliver sustained competitive advantage. The operative word here is sustained, because for the advantage to truly hold over a long time (like Roger Federer’s 300+ weeks at World No. 1, or his two decade long pro career where he has been competing at the top level pretty much all through) the resources that are identified and develop need to posses four qualities. They must be valuable, rare, inimitable and organized to capture value. Let’s look at that idea and see if it can explain how Federer does it. The RBV assumes that the resources we are talking about are heterogenous i.e. they differ from organisation to organisation. Pro tennis players have their idiosyncratic playing styles and strengths and weaknesses, so our analogy holds there. The second assumption is that the resources are immobile – they cannot be transferred from one company to another. Again, a player’s unique skill set cannot really be transferred from one to another. You can’t get Richard Gasquet’s magnificent backhand just because you cut off his hand and attached it to your body. Or, more practically, even if you have the same coach, it will still be well nigh impossible. So, tennis players can be viewed as a bundle of unique resources and capabilities – both mental and physical – competing against each other. Federer’s sustained success, then, can be explained by the RBV and how his capabilities tick all the boxes of being valuable, rare, inimitable and organized.

Valuable

From a young age he was recognized as a prodigy whose superior shot making and aggressive approach made him successful and an electric player to watch. People flocked to watch him, this his capabilities pass the ‘Valuable’ Test (“Resources are valuable if they help organizations to increase the value offered to the customers.”)

Rare

Federer was certainly a rare talent. He was outperforming his age groups by an order of magnitude which is why he could turn pro when he was barely 18. He passes the ‘Rarity’ test too.

Inimitable

Federer’s service game, his blisteringly good forehand and his volleying game were all superbly honed and even his fellow pros as well tennis legends agreed that it was foolishness to think someone could simply copy his style and range. There was only one Federer in terms of the tennis package. Inimitable.

Organized

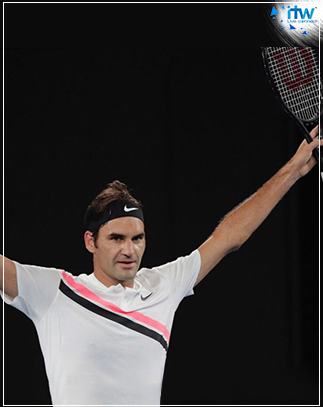

And of course with his support staff, coaches and physio, Federer organized those capabilities into a consummate pro tennis player who obsessed over success. His 20 Grand Slams – most among men all time – and 97 ATP titles – second-most among men all time – are ample proof of that.

But it wouldn’t really be an instructive story if it were just about one man who had all the right resources and succeeded. Federer’s real genius and the key business lesson here is how he plotted his comeback after he lost his No. 1 ranking in 2012. Experts almost unanimously thought that would be the end of Federer. In a sport so physically demanding pros don’t last past their early thirties, certainly nobody wins Grand Slams past 35, and they certainly don’t become World Number One.

Businesses face tough competition the same way and often their competitive advantage wanes away because of emergence of competition. Federer was dethroned as No. 1 in 2008 by Rafael Nadal, who had the perfect antidote to the Swiss maestro’s game. And since then they shared an intense on court rivalry. Federer’s perfect bundle of VRIO resources seemed under threat. So what did he do? After crashing out of Wimbledon in 2013 (he was defending champion), he started making adjustments to his game to account for the competition catching up. His resources were still valuable and to a large extent rare, but the inimitability and his organisation was beginning to look suspect. Usually if that happens, the sustainable competitive advantage becomes a temporary advantage and eventually vanishes. So, companies need to constantly think of how to keep their resources VRIO. Like Federer. He went back to the drawing board. He worked on his weakness – the backhand – and made it a weapon. In 2015, he started experimenting with a strategy of approaching the net and trying to shorten points, a move that was dubbed SABR – sneak attack by Roger. These new tweaks meant that his new game plan was almost unrecognisable compared to the Federer half a decade ago but delivered the same result – wins in tennis matches.

When you’re older you have to work double the amount. You have to wrestle it back from someone who’s worked hard to get there.

Admittedly, he had a lucky break or two, but there are no gimmes in the world of professional sport (just as there are none in business) and he took full toll, winning another three Grand Slam titles and looking set and ready for possibly more.

He said after he reached number one, “Reaching number one is the ultimate achievement in tennis. It’s been an amazing journey and to clinch it here (at Rotterdam), where I got my first wildcard in 1998, means so much.”

His return to the No. 1 spot maybe mathematical symbolism given how the ATP ranking points work, but it doesn’t seem out of place, because at this point he is simply the best player in the world. Federer may not be an avid strategy literature enthusiast, but there is a case to be made for renaming the RBV, the Roger Based View of the firm.